On The Boats…………(Part 1)

December 6, 2014

I watched the snake slither along the wooden rafter of the hut, its black tongue flicking ahead, feeling the way. Lying on my bed and looking up at the bright green reptile I wondered what my escape plan was. It was the first time a mamba had come into our billet but I always knew our luck would run out one day. We were after all in the middle of the bush, working out of Deka Army Base and snakes were quite commonplace. I didn’t like snakes then and I don’t like snakes now. Just one of those things. Anything else I can handle.

Here is a picture of a Green Mamba (greenmambasnake.com)…..a very dodgy visitor indeed:

There were two of us. Both Sappers from 1 Engineer Squadron and attached to the infantry unit at the camp. I think it was 1 Independent Company from Wankie based there most of the time on Border Control operations. Tony Carinus and I were tasked with operating a Hercules Assault Boat within our area of responsibility on the Zambezi River, and our boat was moored with the British South Africa Police (BSAP) boats at the Sibankwazi Police post. We had approximately 60 kilometres of river to patrol which was quite a stretch and we tried to cover this as often as we could.

Our boats were shite-looking and the police boats were all shiny and painted in cute pastel colours with lots of aerials on them so they could listen to Sally Donaldson and Forces Requests on Sundays. Papa5 was a particularly nice police boat that I would have given my left testicle to take onto the river but big John Arkley, the Member-In-Charge of the Sibankwazi BSAP would not allow it. We never had any aerials as we had no one in particular to talk to and the boats were painted a matt dark green, or at least they were green when they were new which must have been in 1945 or earlier.

Here is a picture of one of our boats (Basil Preston):

Please note the warped wooden seats made for extreme anal comfort, and the generally dodgy state of seaworthiness. I must say that this boat at least has engine covers on the twin 40 ponypower Evinrude outboards so is probably a VIP version. A close look at the red fuel tank also indicates it was probably “borrowed” from a civvy fisherman on a long-term basis as ours were a dull drab brown colour. Either that or the QM ran out of camo paint or brushes, or both.

Here is a picture of the area of the Sibankwazi Police Post (www.bsap.org) where we moored up.

Our boat was not allowed under the shelter because there were too many shiny police boats in there. We normally tied up to the left of the shelter near the launching area (see above). Having said that the bobbies were always very good to Tony and I and we had many good piss-ups and braais with them. They were also destined to get me out of some fairly serious shit in the years to come.

Tony and I normally planned our own activities and it seemed in retrospect that the infantry Sunray (OC) at the camp never had much interest in what we got up to all day. Only occasionally would we drop-off or pick-up infantry sticks along the Rhodesian side of the river. This resulted in a lot of tiger fishing, game viewing, stopping off at Msuna Mouth or Deka Drum resorts for beers and a meal, or simply patrolling up and down the river looking for gook crossing points or even better still, some gooks.

This is the Deka Drum area of the Zambezi (Craig Haskins)………

A pretty enjoyable time for me and Tony in general and I have fond memories of my days on the boats. We did however have some dodgy experiences and these will part of the next few posts.

Please also have a look at my website dedicated to Rhodesian and South African Military Engineers. Please join us on the forums by using the following link:

http://www.sasappers.net/forum/index.php

Copyright

© Mark Richard Craig and Fatfox9’s Blog, 2009-2014. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited.

Cordon Sanitaire: Electronic Alarms and Monitoring

August 25, 2014

If I thought that getting historical background to Cordon Sanitaire defoliation efforts (see previous post) was challenging, I was wrong!

Trying to find anyone who has in-depth information on the electronic early warning systems installed on the fences was an even more daunting task. To be very honest I am not in any way convinced that what I have managed to find holds too much water and this is once again where I will be hoping that someone, somewhere reads this post, tells me I have written complete rubbish and puts things right. I can take it and no offence will be taken I assure you. We simply need to get this as factual as we can. There has to be Rhodesian Army veterans that actually installed and monitored the electronic side of things that can help here.

The following redaction comes from more than one source, the reliability of which has not been confirmed to me. From an intelligence source and reliability perspective I therefore have no option but to rate it as F/6 (Insufficient information to evaluate reliability. May or may not be reliable/The validity of the information cannot be determined) and should therefore by no means be quoted as being the way things actually were. Read on………..

For the sake of simplicity we will consider the Cordon to be 25 metres wide, fenced on both sides, and containing anti-personnel blast mines.

On the home side a system of electronic sensors divided into monitored sectors and wired to sector control boxes formed the basis of the early warning system. I have not been able to find any information as to what type of sensors (movement, vibration, broken electrical circuit, audio, etc.) were used, nor who was responsible for installing them (possibly the Rhodesian Corps of Signals (8 Signal Squadron)). According to one source these control boxes were placed in bunkers close to the home side fence and manned full-time by troops waiting for an alarm to be set off.

Logic makes me think that a combination of activation triggers may have been used. Apparently the idea was that any penetration of the Cordon would be detected by detonations or some form of electronic sensor. My information claims that reaction to these events was primarily by vehicle and took place within 10 minutes of a signal being received. In addition to the vehicular response, artillery fire was also used to put down fire on ranged, pre-selected targets. I imagine this would be from 25 pounder howitzers or possibly 120mm mortars.

It is my understanding that the only parts of Cordon Sanitaire to be fitted with an electronic early warning system were the Musengezi/Mukumbura, and Nyamapanda to Ruenya minefield. Soon after these areas were completed a significant amount of false alarms were being recorded. This resulted in finding no enemy presence at the alarm trigger point. Due to the significant cost of ammunition being expended on these false-positive events, it was decided to curtail the rapid response on these areas in 1975. An ongoing Cordon Sanitaire review shelved the whole idea of an early warning system shortly thereafter.

And so ended the Cordon Sanitaire early warning system.

I do not know how effective these measures were as I never encountered them during my time serving in the Rhodesian Corps of Engineers. Personally I do not think the electronic system was as successful as the planners initially thought it would be and with the Rhodesian economy heavily burdened by sanctions and an ever-increasing defence budget there was little chance of any project surviving unless it showed significant success indicators (body count, infiltration mitigation, etc.).

I located the following on the issafrica.org website. They seem to confirm in some ways parts of the foregoing:

I will continue to seek further sources to help unravel this interesting and little known subject.

Please also have a look at my website dedicated to Rhodesian and South African Military Engineers. Please join us on the forums by using the following link:

http://www.sasappers.net/forum/index.php

Copyright

© Mark Richard Craig and Fatfox9’s Blog, 2009-2014. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited.

Cordon Sanitaire: Defoliation Efforts

July 26, 2014

I never realised how challenging it would be to get information on Rhodesian Army defoliation efforts on Cordon Sanitaire or anywhere else for that matter. One of the main reasons for this is that these activities took place, and were more or less completed by the time I joined the army. It is disappointing that so little is known of these activities and I apologise in advance for the scant information at hand. This is definitely one of those posts where I could do with all the help I can get.

However I have managed to cobble some data together thanks to Terry Griffin and Vic Thackwray (a big thanks to both of them who incidentally were also both my Commanding Officers, at different times of course), and also a number of publications. It would however seem that very little information on this aspect is available.

As a starter to this post it is probably useful for some readers to have a better understanding of what defoliation is all about, why it is used during military operations, the main methodologies used, and historical results both positive and negative. Without question the use of defoliant by the US military during the Vietnam War (and Korea before that) is the best example of these activities and they are well documented, mainly for all the wrong reasons.

A short preamble will therefore follow and we will then look at Rhodesian Army efforts according to my understanding of things.

Chemical Defoliation

Probably the most well-known chemical defoliant used to date is Agent Orange.

Agent Orange was a powerful mixture of chemical defoliant used by U.S. military forces during the Vietnam War to eliminate forest cover for North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops, as well as crops that might be used to feed them. The U.S. program of defoliation, codenamed Operation Ranch Hand (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Ranch_Hand), sprayed more than 19 million gallons of herbicides over 4.5 million acres of land in Vietnam from 1961 to 1972. Agent Orange, which contained the chemical dioxin, was the most commonly used of the herbicide mixtures, and the most effective. It was later revealed to cause serious health issues–including tumors, birth defects, rashes, psychological symptoms and cancer–among returning U.S. servicemen and their families as well as among the Vietnamese population.

Above picture shows a four-plane defoliant run, part of Operation Ranch Hand (wikipedia)

Agent Orange was the most commonly used, and most effective, mixture of herbicides and got its name from the orange stripe painted on the 55-gallon drums in which the mixture was stored (see picture below). It was one of several “Rainbow Herbicides” used, along with Agents White, Purple, Pink, Green and Blue. U.S. planes sprayed some 11 million to 13 million gallons of Agent Orange in Vietnam between January 1965 and April 1970. According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Agent Orange contained “minute traces” of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), more commonly known as dioxin. Through studies done on laboratory animals, dioxin has been shown to be highly toxic even in minute doses; human exposure to the chemical could be associated with serious health issues such as muscular dysfunction, inflammation, birth defects, nervous system disorders and even the development of various cancers.

Photo and parts of the above paragraphs in italics are from http://www.history.com/topics/vietnam-war/agent-orange.

We should also be clear here that the US were not the only ones using Agent Orange. This interesting fact is expanded on below:

The British used Agent Orange in Malaya, but for the very British reason of cutting costs…The alternative was employing local labor three times a year to cut the vegetation. British stinginess over this matter in one respect helped to avoid the controversies provoked by the use of Agent Orange in Vietnam. The original intention was to crop spray but even this was deemed too expensive by the protectorate authorities. Eventually someone struck on the idea of simply hosing the jungle from the back of bowser trucks and this is what the British did, in limited areas and to no great effect. This happily amateur effort at chemical warfare undoubtedly saved future British governments from the litigation suffered by post-Vietnam US governments (http://www.psywarrior.com/DefoliationPsyopVietnam.html).

In fact the US were largely inspired to use chemical defoliation from the good old Brits.

Mechanical Defoliation

Mechanical defoliation makes use of heavy earth moving machinery to excavate, bulldoze or scrape vegetation out of the ground. This cannot be considered as permanent a method as using chemical agents but it has the advantage of being localised to where the machinery is being used. Crucially it does not spray poisonous herbicides from here to eternity, or cause long-lasting sickness and disease.

Deduction

So from the above two methodologies we can determine that the main use of defoliation was to:

a. Deny the enemy cover to attack from

b. Deny the enemy the ability to grow crops to feed themselves with

c. For Cordon Sanitaire purposes it also had the added use of allowing us cleared areas in which to lay mines

Rhodesian Army Defoliation Efforts

The Rhodesians used a combination of mechanical and chemical defoliation methods on Cordon Sanitaire and Non-Cordon Sanitaire operations.

So Rhodesia was apparently not squeaky clean as far as using herbicides was concerned although very little is known of their use, or the extent of such use. There is also no objective evidence that shows what if any residual effect there was on the local population and indeed our own troops. Perhaps this is an aspect that no one wants to talk about or perhaps it was just one of those activities no one knows much about. Somehow I have a feeling there is someone out there who knows a lot more about this activity.

I managed to dig up the following and once again I apologise for the lack of real meat for this post:

The Rhodesian Corps of Engineers were responsible for clearing the 25 meter wide strip of land that would eventually become the minefield with bulldozers. This mechanical defoliation methodology was used primarily to make the job of laying mines easier and to make the terrain more suitable in general for manual, dismounted operations. Laying mines in vegetated areas is both dodgy and dangerous. One can very easily become disoriented with disastrous results.

The Tsetse Fly Department (the “Fly-Men”…….see previous posts) were apparently responsible for the Rhodesian chemical warfare effort. I found this very surprising when I read about this but it appears to be quite true. Apparently they used back-pack hand-operated sprayers containing HYVAR-X. (PRODUCT INFORMATION: DuPont™ HYVAR® X herbicide is a wettable powder to be mixed in water and applied as a spray for non-selective weed and brush control in non-cropland areas and for selective weed control in certain crops. HYVAR® X is an effective general herbicide that controls many annual weeds at lower rates and perennial weeds and brush at the highest rates allowed by this label. It is particularly useful for the control of perennial grasses). You can read more about HYVAR-X at http://www.afpmb.org/sites/default/files/pubs/standardlists/labels/6840-01-408-9079_label.pdf

It seems that the Cordon Sanitaire planners were not happy with only a 25 meter defoliated corridor and gave orders to chemically remove vegetation 150 meters either side of the Cordon fences (I have to wonder how this was achieved using back-pack hand-operated sprayers). In a bid to save on costs they substituted HYVAR-X with a different chemical known as TORDON 225. This would prove to be a costly mistake as this product was ineffective and resulted in Rhodesia instituting court action against the South African manufacturers of TORDON 225.

I found only one record of chemical defoliation usage. This was apparently on the Musengezi, Mukumbura, and Nyamapanda to Ruenya minefield. Nothing else is available.

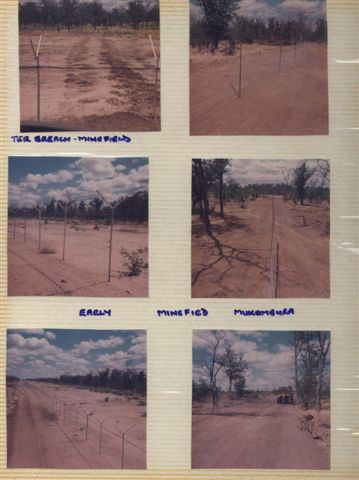

The following two photos were sent to me by Vic Thackwray, a Cordon Sanitaire veteran. They show the cleared areas between the minefield perimeter fences. In the first picture the minefield is on the left of the fence. A parallel minefield maintenance road can be see on the right of the fence. This specific photo was taken at Mukumbura.

The second photo is a great shot of Vic Thackwray standing next to the Cordon fence. Note the thick vegetation inside the mined area.

I also have some interesting input from Terry Griffin which I have added below:

The photos above were provided by Terry. They too show the type of terrain and vegetation of the Cordon at Mukumbura. I must add the terrain was not always as good as what is shown and from my own experience this was as good as it got (so don’t think we had it easy all the time).

Terry also highlighted some non-Cordon defoliation and I felt it was appropriate to include in this post. It makes very interesting reading. Terry takes up the story:

The very first minefield laying etc (again) I was OC of that – starting at Mukambura. Lt Col Horne actually came up with the team I had trained – for a look see.

Tsetse were (as per normal) responsible for erecting fences but we also had plant tp folk with bulldozers and graders clearing all so we had bare earth in and outside the minefield to work on. This was also to prevent gooks taking cover in the bush. At that stage the minefield was approx. 25m wide. In no time I realised this method was an absolute waste of time money etc, etc as we also provided armed protection for the dozer drivers etc way ahead of laying teams. To keep a definitive 25m width etc was patently stupid so I wrote a paper and suggested fences meander to create doubt as to depth of field – albeit still 3 rows – and do NOT clear vegetation as it then aided in camouflaging all. I sent you some pics of the first gook breach and just look at the nice clear earth with fences visible at exactly 25m. Boy did we have a lot to learn – and quickly. This is the only defoliation that I am aware of??

And after I prodded him for more:

Basically I was tasked with doing the defoliation on Chete Island after the gooks wacked the civvy ferry. I called up S Tp from 1 Sqn albeit I was OC Boats at the time and then we sailed plus Tsetse in the Army ferry (Ubique) from Kariba to Chete. Had strike craft as back up and positioned one at each entry to the gorge as it had been declared a frozen area for all craft during the OP. Went ashore (after anchoring on the island – invading enemy territory !! – to clear it of gooks – if any. There were none. Tsetse also provided back up (Jack Kerr plus another) with ,458 rifles in case elephants had a go at us. They did not. After positioning the guys in a defensive role we cleared the area where the gooks had fired from – onto the ferry – which still had much kit lying around from the firing point. Tsetse folk then used a defoliant called Hivar (as I recall) and by hand distributed like it was fertiliser along the entire bank facing the gorge and inland a short way. This would (as it did) clear that sector of all foliage and thereby (hopefully) deny natural cover. After the first rains it was evident all was dying off and it did clear all fairly quickly creating a rather bare scar along that section of the island. Some 10 years later it was still very visible but on my last fishing trip there + – 4 years ago all had now regrown. The gooks never did use the original firing position again.

Looking at this post I realise that although I would have liked to give the reader more on the actual defoliation in Rhodesia, what we have here is real Rhodesian Millitary Engineering history. The accounts by Terry have probably never been recorded in this format before and the photos from Vic still give me goose-bumps, bringing back a part of my history that must be told or it will be gone forever. Thanks to both of them once again for all the help and support they provide to me.

I would like to end this post with a cruel irony:

Perhaps no two people embodied the moral complexities and the agony of Agent Orange more graphically than Adm. Elmo R. Zumwalt Jr. and his son Elmo R. Zumwalt III. Admiral Zumwalt led American naval forces in Vietnam from 1968 to 1970, before he became chief of naval operations. He ordered the spraying of Agent Orange. The son was in Vietnam at about the same time as the father, commanding a Navy patrol boat. Years later, doctors found that he had lymphoma and Hodgkin’s disease. He died in 1988 at 42. His son, Elmo IV, was born with congenital disorders.

Perhaps this post has digressed a bit from the title but it does make for interesting reading I hope.

In the next post we will look at Cordon Sanitaire with electronic alarms.

Copyright

© Mark Richard Craig and Fatfox9’s Blog, 2009-2014. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited.